design

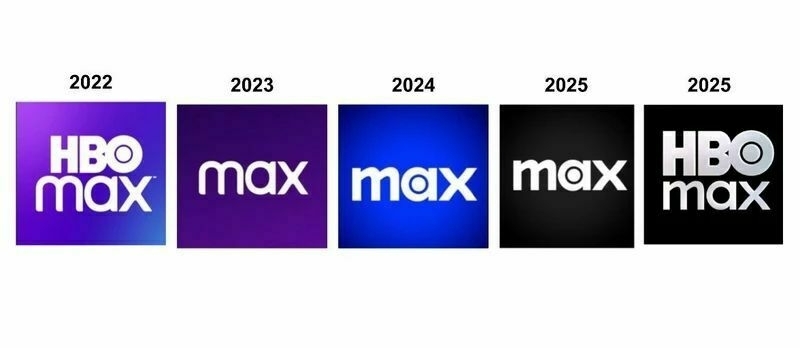

Iteration is good, actually. Listening to your customers is good, actually. Fixing a mistake quickly is good, actually.

Too many brands and products remain stagnant, ignore their users in favor of the whims of their leadership, and let pride and the sunk cost fallacy prevent them from doing the obviously correct thing.

Bravo, HBO Max.

When discussing usability testing with clients and stakeholders, I often say “If you’re doing a week of testing, you’ll learn most of what you’re going to learn by lunchtime on the first day.” A bit cheeky, but true in my experience.

As it turns out, NN/g has done the research to support my claim.

I don’t dream of labor, but if I did, working for 18F would have been a dream job. Their work raised the bar for what citizens can and should expect from government technology. They saved taxpayers billions of dollars. And, thanks to their open-first philosophy, their contributions to the disciplines of human-centered design and software development are immeasurable.

The concept of “running government like a business” is deeply flawed, because it misunderstands the purpose of both. But, in terms of efficiency, excellence, impact, and value, it would be hard to beat the 18F model.

I hope those impacted quickly find new opportunities, and I invite you to join me in demanding that that our elected officials immediately address the outrageous circumstances that led to 18F’s closure. We all deserve better.

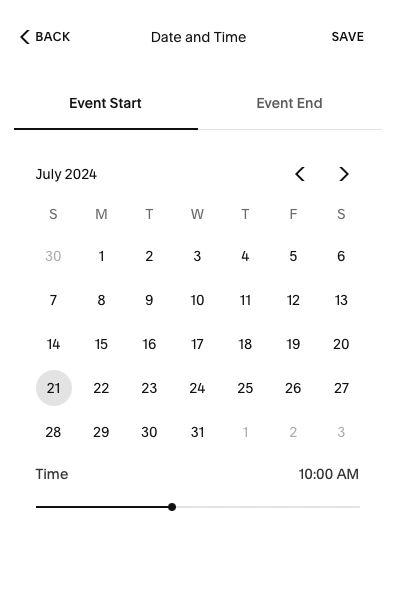

Squarespace’s Events feature has to win the award for “Most Unhinged UI Element, Time Picker.” Behold:

Three candidates have announced their 2024 candidacy for Delaware’s lone U.S. House seat. How did they use branding to differentiate themselves in an already crowded field?

In the next installment of “The Politics of Design,” I critiqued all three for the Delaware Call.

I’m in the Delaware Call today!

The Politics of Design will be a lighthearted series of critiques focusing on the branding of state and local politicians.

First up: the logo for Delaware gubernatorial hopeful Matt Meyer.

Three Weird Tricks That Might Help Your Sketching (or not)

They might not work for you, though, and that’s okay!

Sketching remains a vital part of the design process here at Arcweb Technologies, and has been incredibly transformative for me, personally:

I can honestly say that buying into a process that includes both sketching and prototyping has exponentially leveled up my game this year. — Len Damico (@lendamico) on December 11, 2014

Any old writing instrument and paper can work for sketching. It’s an incredibly open-ended discipline, and that’s part of the beauty of it! But as I’ve sketched more and more, these three simple things have made my the time I spend on it much more productive.

Dots, Not Grids

Graph paper can help make your layouts feel more like precision documents than rough doodles, but not all graph paper is created equal. Some variants have lines so dark that you struggle to see your sketches on it.

The secret: find dotted graph paper rather than lined. The dots allow for some precision and alignment, but don’t compete with your sketches. (I personally love these hard-backed notebooks from Baron Fig, which are available with dotted pages.)

Commit to the Pen

Typically, sketching happens with a pencil. In fact, every designer gets a beautiful Alvin mechanical pencil when they start at Arcweb Technologies. But while pencil has its place, consider giving pen a shot for your next sketch session. In my experience, the fact that pencil sketches are erasable becomes more bug than feature. A pen forces me to always keep moving, not stopping to erase mistakes. Plus, a pen’s indelibility makes for a good reminder to move forward and save all ideas, instead of erasing as you go.

Invest in a Date Stamp

As I look back through my sketching journal, the days often run together. I’ve tried dating pages by hand, but those hand-written dates tended to blend with the actual sketches on the page. The solution, borrowed from Philadelphia artist Mike Jackson, was to invest in a tiny date stamper. The stamps feel official and important but its true value is that it stand out from everything else on the page. Plus, there’s a certain Zen-like quality to the process of stamping today’s date at the top of a blank page.

To Each Their Own

These hacks came from spending lots of time sketching, finding out where my own friction points were, and removing them as simply as I could. They may or may not work for you, and that’s okay! If you’ve got your own sketching tricks, tweet them at me and I’ll share them around. Good luck, and happy sketching!

Hail To The (New and Improved?) Lion

Let’s start our discussion of Penn State’s new academic logo with critiquing the work itself, before we dive into critiquing the process.

The mark itself? It’s… boring. Corporate. Safe. Could be a bank, could be a hospital. The rendition of the lion itself is fine. I don’t love the 2-Color approach, and that’s going to be a real pain to embroider, but it’s fine. The type itself is also fine. Very contemporary, and again, very safe.

The move to a more neutral, middle-of-the-road shade of blue is disheartening. Again, could be a hospital, could be a bank.

I get why the existing mark needed some time in the shop, but compared to this new mark, it feels even more timeless.

Maybe my comments on the new mark being corporate and safe are off the mark. Maybe that was a stated goal in the brief. I don’t know! Penn State is among the largest research institutions in the nation. Maybe a boring, corporate brand will serve them better in the long run.

But as an alumni, this new mark leaves me full of… meh. Just, meh. No visceral reaction whatsoever.

And maybe I feel so positively about the old mark because I’ve been seeing that thing since I was born. But, if you take away the Lion statue, you take away 1855, you take away that beautiful type that looks carved in stone… you better give me something really, really good in return.

To be clear, I’m laying the blame for this squarely at the University’s feet. I’m sure the firm did some great work that died in committee. For example, this is a recipe for disaster: “More than 300 members of various faculty, staff and administrative groups were engaged during the process.“ And seriously, please miss me with “they spent $128k on THIS?!??!” That’s a drop in the bucket for a rebrand effort of this scale. (If we really want to get Nit-picky (see what I did there?), I think it’s fair to ask why the University couldn’t find a PA firm qualified to do this.)

Overall, the whole thing is boring, corporate and safe. Underwhelming. I expected better from something like this, but maybe that’s my fault. Thanks for listening. We are Penn State.

(One last thing: You can change the chipmunk logo after you pry it from my cold, dead hands.)

The purely aesthetic form

I’m about halfway through Jony Ive: The Genius Behind Apple’s Greatest Products. So far, it’s a good read. It portrays Ive as someone with exquisite taste who was in the right place at the right time, willing to work harder and care more than his competitors. It never descends into hagiography (in spite of the sub-title), as many tech bios tend to do.

Author Leander Kahney goes to great lengths throughout to express Jony’s distaste for “skinning” a product (applying surface-level design to something engineering had already created). In Ive’s design-centric mind, the “inside-out” method lead to compromised products.

But let’s square that with this tale from the design of the original Mac Mini:

The decision about the size of the case might seem trivial, but it would influence what kind of hard drive the Mini could contain. If the case were large enough, the computer could be given a 3.5-inch drive, commonly used in desktop machines and relatively inexpensive. If Jony chose a small case, it would have to use a much more expensive 2.5-inch laptop drive.

Jony and the VPs selected an enclosure that was just 2 mm too small to use a less expensive 3.5-inch drive. “They picked it based on what it looks like, not on the hard drive, which will save money,” [former Apple product design engineer Gautam] Baksi said. He said Jony didn’t even bring up the issue of the hard drive; it wouldn’t have made a difference. “Even if we provided that feedback, it’s rare they would change the original intent,” he said. “They went with a purely aesthetic form of what it should look like and how big it should be.”

This is… well, it’s not design.

Design is solving problems within constraints. The characteristics of components, including price, are constraints. Without having a damn good reason to make the case 2 mm too small to fit a much less expensive 3.5-inch hard drive, you’re just decorating and playing artist, not designer. This is even more surprising, given that Ive is notorious for knowing and waxing rhapsodic about every last detail of his materials.

Outside-in product development is just as problematic as the inside-out approach that Ive despised. In this case, it may have led to a product that was more expensive (or less profitable) than it needed to be. Given that one of the Mac Mini’s core benefits as an entry-level Mac was its low cost, this is baffling.

Great product development is a true partnership between engineering and design.

(Yes, I know. Jony Ive is perhaps the most celebrated industrial designer in the history of the field, and rightly so. And Apple has a track record of ignoring practical decisions in the pursuit of a product’s true essence. That doesn’t mean we can’t examine a particular design challenge they faced and learn from it.)

Why We Prototype

Here at Arcweb, we’ve been spending more time using analog methods of exploring and communicating our ideas and we’ve augmented our UI design process with Sketch.app. The next piece of the Arcweb design process that we’ll explore is prototyping.

What is Prototyping?

In our context, prototyping is the process of efficiently creating a representation of a digital product that reflects our current vision of it. Prototypes are meant for learning and communicating, not perfection. They can vary in fidelity from simple, ad-hoc paper prototypes to complex, clickable versions that are almost indistinguishable from real, working software. Efficiency is key here; we create the prototype to learn more about our assumptions and how a piece of software might work before actually building the software.

Why Prototype?

Prototyping helps us build customer value from the day we begin the Discovery process on a project. More specifically, it facilitates three types of communication that contribute to building the right product for the problem at hand:

The Designer’s Inner Monologue

The closer something is to “real,” the easier it is to evaluate. Consequently, that’s not the case for what’s in a designer’s head. What’s in a designer’s head is, in fact, the furthest thing from “real” there is. But a prototype changes all that. By prototyping, we are able to iterate quickly through ideas that won’t work without sending other departments (like development) on missions built to fail. Said differently, rapid, iterative prototyping allows the design team to fail fast which in turn will bolster confidence because everything’s been considered.

Designer-Developer Collaboration

Prototyping also facilitates more effective designer-developer collaboration. With prototypes, the design team is able to show the development team what’s to be built rather than simply telling them. (This is valuable for both practical and interpersonal reasons.) Some prototyping tools even allow developers to pull snippets of code that they can use to get started or in production.

By prototyping, we reduce the frustration and ambiguity that can occur when designer and dev terms don’t make sense to the other. For example, when the design team prototypes, devs don’t have to guess at what a phrase like “the sidebar dances in” means. Instead they see it. (By now it should be abundantly obvious that prototyping minimizes engineer grumpiness.) And when they see it, developers can provide rich, insightful feedback, assess technical feasibility and system design and cut excess scope earlier in the process.

Customer Dialogue

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a prototype is worth a thousand meetings. Prototyping allows us to build consensus with our customers earlier in the life of a project. As much as a customer can say they “get it” from reviewing flat comps, prototypes that look and feel like real software allow for deeper, richer understanding. Throughout the life of a project, that means fewer surprises and the less-than-comfortable conversations you have to have when they spring up.

Finally, customers tend to be more vocal when it comes to raising issues when they’re looking at a prototype versus live software. And this makes sense: no matter if it’s a small modification or a complete pivot, change requests after multiple dev sprints are expensive. They are far less so in the prototyping stage. (Think hours instead of weeks or months.)

So that’s why we prototype. It improves how designers communicate their visions. It aligns designer-developer relationships and workflows. And it helps customers better understand what will be built before it’s built.